MILENA STERIO

Major human rights treaties, international criminal law documents and other instruments recognize that juvenile suspects need to be treated distinctly within any criminal investigation or prosecution. This post will explore different human rights protections extended to children who may be suspects in a criminal proceeding. The treatment of children within penal systems of various nations is relevant in many different contexts, but has arisen most recently in the context of maritime piracy prosecutions involving juvenile suspects, where children may be the subject of pre- and post-trial detention and/or criminal proceedings. The discussion and recommendations explored in this post will focus on the prosecution of maritime piracy suspects, but these recommendations are applicable more generally and should concern all types of criminal proceedings initiated against children.

Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility

Most family law and human rights law experts and many states agree with the idea that each individual needs to reach a minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) before he or she can be held accountable for his or her actions. While the concept of MACR has received near universal acceptance, neither family nor international law have ever established a generally agreed upon precise age at which one would incur criminal responsibility. As of today, 174 states have established a MACR, and establishing a MACR is required by major human rights instruments. Article 40(3)(a) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) requires that:

States Parties shall seek to promote the establishment of laws, procedures, authorities and institutions specifically applicable to children alleged as, accused of, or recognized as having infringed the penal law, and, in particular: (a) The establishment of a minimum age below which children shall be presumed not to have the capacity to infringe the penal law.

In addition, Article 4.1 of the United Nations Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (Beijing Rules) states that that MACR “shall not be fixed at too low an age level, bearing in mind the factors of emotional, mental and intellectual maturity”. General Comment No. 10, issued by the Committee on the Rights of the Child in 2007, entitled “Children’s rights in juvenile justice,” further clarifies the meaning of Article 40(3)(a) of the CRC, cited above. Citing Article 4 of the Beijing Rules, General Comment No. 10 concludes that state parties to the CRC should not set their respective MACRs below the age of twelve, because this would not be “internationally acceptable”. General Comment No. 10 thus establishes the age of twelve as the threshold MACR and further encourages state parties to the CRC to consider increasing their national MACRs to higher levels.

These instruments reflect that the underlying policy goal of international justice should be to determine the minimum age at which an individual has sufficient moral, intellectual, and emotional maturity in order to bear criminal responsibility. However, the above-cited instruments also demonstrate that states are currently free to determine such a minimum age according to their own national laws and policies. Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in a tremendous disparity of MACRs at the national level. According to General Comment No. 10, cited above, state parties to the CRC have reported that their national MACRs range from seven to sixteen years of age.

At the international criminal tribunal level, MACRs vary from one international body to another. The statutes of the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) do not mention a particular MACR, although in practice, neither of the tribunals has ever prosecuted a defendant under the age of eighteen. It is thus unclear whether the Statutes of these two tribunals purposely omitted a provision establishing an MACR, thereby indicating that the Tribunals were unwilling to prosecute anyone under the age of eighteen, or whether the omission can be interpreted as allowing these Tribunals to prosecute juveniles.

Article 6 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) specifically excludes individuals under the age of eighteen from the court’s jurisdiction, but the Rome Statute does not specifically mention a MACR (“[t]he Court shall have no jurisdiction over any person under the age of 18 at the time of the alleged commission of a crime.”). The Statute for the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) does not establish a clear MACR either; instead, the Statute incorporates Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which states that in case of juveniles, any judicial procedure should take into account their age and the desirability of promoting their rehabilitation. The Statute of the Special Court for Sierra Leone establishes an MACR of fifteen, and provides that juveniles between the ages of fifteen and eighteen may be prosecuted by the court but that they should be treated distinctly, and in accordance with international human rights relative to the rights of the child. Finally, the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) establishes a clear-cut MACR at the age of twelve, and provides for special treatment for juveniles between the ages of thirteen and sixteen.

It appears that international law obliges states to establish an MACR, but that it does not provide much guidance about what the specific MACR should be. In light of General Comment No. 10, it may be argued that the trend in international law may be toward establishing national MACRs in the mid-teens. However, it may also be argued that the Rome Statute of the ICC and the CRC clearly establish an emerging consensus that children should be shielded from criminal liability altogether. One could conclude that at a minimum, international law instruments, such as the CRC and its General Comment No. 10, as well as the Beijing Rules, and the statutes of various international criminal tribunals seem to suggest that MACR should not be set an age lower than twelve.

International Human Rights Law on the Treatment of Juvenile Suspects

In addition to determining an appropriate MACR, any nation contemplating the prosecution of juvenile suspects must also determine which international treaties and other instruments create additional binding norms, which apply specifically to the treatment of juveniles. It should be noted that all norms of international human rights law apply equally to adults and to juveniles. For example, fundamental principles of internationa

l criminal law, such as nullum crimen sine lege, apply equally to children as it does to adults. However, other human rights provisions specific to the rights of children establish that juvenile suspects in all judicial proceedings must be provided with greater protections that go beyond the minimum standards of treatment afforded to adults.

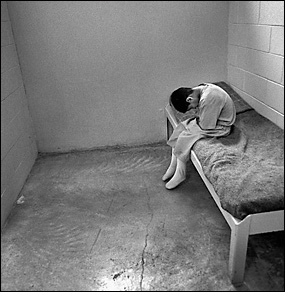

Source: Downton and Clark, PLLC

Two different International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights’ articles specifically address the rights of juvenile suspects. Article 10(2)(b) addresses the rights of juveniles in the context of pre-trial detention, by providing that “[a]ccused juvenile persons shall be separated from adults and brought as speedily as possible for adjudication”. Article 10(3) similarly requires that if convicted, juvenile offenders “shall be segregated from adults and be accorded treatment appropriate to their age and legal status”. In addition, Article 10(3) requires member states to generally take into account a juvenile’s age throughout his or her encounter with the penal system. Article 14(4) builds on the requirements of Article 10(3), by stating that any judicial proceedings applied to juveniles should take into account their age and “the desirability of promoting their rehabilitation”. Article 14(1) further specifies that where the interests of the juvenile would be better served if his or her sentence were kept confidential, the authorities of the relevant state should not render his or her sentence public. In conclusion, the ICCPR requires member states to consider the juvenile suspect’s age at all stages of judicial proceedings, starting with pre-trial detention and ending with sentencing.

In addition to the ICCPR, an important norm of international humanitarian law dealing with children involved in armed conflict and expressed in the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions pertains to the treatment of juveniles. Article 77 of the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions specifies that “[i]f arrested, detained or interned for reasons related to the armed conflict, children shall be held in quarters separate from the quarters of adults”. According to the International Committee on the Red Cross, Rule 120 of customary international humanitarian law espouses the same idea as Article 77 of the Additional Protocol I, that children should be detained separately from adults: “Children who are deprived of their liberty must be held in quarters separate from those of adults, except where families are accommodated as family units”.

Like the ICCPR, Additional Protocol I, as well as customary international humanitarian law, impose a duty on all member states to detain juvenile suspects separately from the adult ones; to the extent that this treaty and accompanying customary law can be used by analogy in the non-armed conflict context, they would impose a duty on prosecuting states to provide for distinct detention facilities segregating juvenile suspects from adults.

The CRC is the most widely ratified human rights treaty in the world. The CRC is a specialized human rights treaty which focuses on the rights of children—those defined by this treaty as a “human being below the age of 18 years unless, under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier”. Article 3 of the CRC establishes that in all aspects of juvenile treatment, including court proceedings, “the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration”. This is particularly relevant in the context of criminal proceedings, where other policy considerations of retribution, deterrence, and rehabilitation may carry equal weight within different jurisdictions. According to the CRC, if a child is the subject of a criminal proceeding, rehabilitation should be more important than retribution or deterrence because of the “best interest of the child” approach of this treaty.

Several provisions of the CRC address the rights of juvenile suspects once they have become the subject of a criminal investigation or proceeding. Article 40 requires that member states establish a MACR, as mentioned above, and that:

A variety of dispositions, such as care, guidance and supervision orders; counseling; probation; foster care; education and vocational training programmes and other alternatives to institutional care shall be available to ensure that children are dealt with in a manner appropriate to their well-being and proportionate both to their circumstances and the offence.

Article 12 establishes that every child has the right to be heard, particularly in judicial and other proceedings, either directly or through a representative. According to General Comment No. 10, “to treat the child as a passive object [during judicial proceedings] does not recognize his/her rights nor does it contribute to an effective response to his/her behavior”.

Article 37 details a list of particular protections that a juvenile is entitled to during any judicial proceedings, including immunity from capital punishment or life sentences without the possibility of parole, that detention of a child should only be imposed as a matter of last resort, that juveniles should be incarcerated separately from adults, and that juveniles have the right to contact their parents or guardians. Thus, like the ICCPR, the CRC imposes on its member states a general duty to treat juvenile suspects distinctly from adult ones, by, for example, detaining the former separately from the latter and by requiring states to take a child’s age into account during the entirety of judicial proceedings.

In addition to the above-mentioned human rights treaties, other international law documents reference the need to treat juvenile suspects differently from adult suspects. These instruments include the Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child of 1924, the Beijing Rules, the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of Their Liberty, and the United Nations Guidelines for the Protection of Juvenile Delinquency (Riyadh Guidelines).

The Geneva Declaration on the Rights of the Child was adopted by the League of Nations in 1924. Its main purpose was to establish a duty protection on behalf of all mankind toward children. To this effect, the Declaration contains five different provisions, which require that children be given opportunity, nourishment, and relief. The above-mentioned Beijing Rules were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1985; they include rules and corresponding commentary regarding various aspects of juvenile justice, such as guidance as to the investigation and prosecution of juveniles, guidance with respect to treatment of convicted juveniles, guidance about the investigation of juvenile suspects, etc. The United Nations Rules for the Protection of Juveniles Deprived of their Liberty was also passed as a General Assembly Resolution in 1990. These rules pertain to the issue of detention of juveniles, such as pre-trial detention, the management of juvenile detention facilities, and the treatment of juveniles by personnel working with juveniles in such detention facilities. Finally, the Riyadh Guidelines were adopted as a General Assembly Resolution as well, alongside the Beijing Rules. These guidelines relate to the ways in which states treat children and are aimed at encouraging states to adopt social policies, legislation, and other programs related to children in order to ensure that children become productive members of their respective societies. These guidelines emphasize that, “all aspects of society, from the family to the school to the local community to mass media, have a role to play in preventing juvenile delinquency”.

In sum, the Declaration, Rules and Guidelines mentioned above establish a level of consensus within the international community that states owe a duty of protection toward juveniles, that juveniles should be provided with meaningful educational and other societal opportunities, in order to prevent them from engaging in delinquent behavior, and that, if juveniles have entered the criminal process, their cases be treated in a distinct manner which respects their young age. The documents discussed above appear to be consistent with the CRC and other human rights treaties and customary law requiring similar treatment of juvenile suspects and offenders.

In sum, the Declaration, Rules and Guidelines mentioned above establish a level of consensus within the international community that states owe a duty of protection toward juveniles, that juveniles should be provided with meaningful educational and other societal opportunities, in order to prevent them from engaging in delinquent behavior, and that, if juveniles have entered the criminal process, their cases be treated in a distinct manner which respects their young age. The documents discussed above appear to be consistent with the CRC and other human rights treaties and customary law requiring similar treatment of juvenile suspects and offenders.

In addition, it can be concluded that international law imposes a duty on states to seek rehabilitation and reintegration of the child when imposing a criminal sentence on him or her. Both the ICCPR and the CRC embrace the goal of rehabilitation in any criminal proceedings involving a child, and the CRC adopts a specific “best interest of the child” standard in guiding any such criminal proceedings. Standards of juvenile justice, as discussed above, require any prosecuting authority to give primary consideration to a child’s well-being and to emphasize education and rehabilitation in any sentencing structure.

Implications for the Treatment of Juvenile Piracy Suspects

Juvenile piracy suspects are most often captured on the high seas, after an unsuccessful piracy attack is repelled by a major maritime nation. They do not carry identifying documents and are unable to appropriately verify their juvenile status claim. As this author has written elsewhere, prosecuting authorities of countries such as Germany, Italy, France, India, Malaysia, the Seychelles, and the United States have already dealt with this issue, and have adopted different approaches toward ascertaining age and toward establishing the most appropriate legal regime for juvenile piracy suspects. In light of the various international law instruments described above, it is every state’s duty to grant procedural and substantive protections to all juvenile piracy suspect, in light of their young age and the desirability of their potential rehabilitation.

All states prosecuting piracy suspects who allege juvenile status should first conduct appropriate medical and forensic tests to ascertain the suspects’ ages more accurately, if age is contested. Such procedures include bone and dental X-rays, ultra sounds, MRIs, general physical examinations, as well as cognitive and psychological tests. If a suspect’s age remains uncertain, all prosecuting states should adopt a presumption in favor of juvenile status. This presumption is already supported by General Comment No. 10, which provides that “[i]f there is no proof of age, the child is entitled to a reliable medical or social investigation that may establish his/her age and, in the case of conflict or inconclusive evidence, the child shall have the right to the rule of the benefit of the doubt”. If a piracy prosecuting state determines that a suspect is a juvenile, this suspect should be immediately separated from any detained adults and imprisoned in an appropriate juvenile facility; his case should be transferred to a juvenile court and his treatment and eventual punishment, if applicable, determined while taking into account his young age, while providing appropriate rehabilitative and educational opportunities, and while generally protecting his dignity.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that when taken together, norms of international human rights law and international criminal law impose a duty on all states to establish a MACR. While there is no consensus within the international community as to the specific age that criminal responsibility should attach to juveniles, it appears that most states would agree that MACR should not be set lower than twelve years of age. In addition, the above discussion clearly demonstrates that international law instruments impose a duty on all states which subject juveniles to judicial criminal processes to treat juvenile suspects with special care, to detain them separately from the adult incarcerated population, and to only impose punishments which allow for appropriate rehabilitation opportunities. Finally, the above-discussed international law clearly imposes a duty on states to consider the juvenile suspect’s rehabilitation and overall well-being when imposing any criminal sentence.

These concerns apply with equal force in the context of piracy prosecutions. Because juvenile claims by piracy suspects are often unsupported by documentary evidence, all piracy-prosecuting states should conduct appropriate age determinations to identify juvenile suspects, any time juvenile status is alleged by one of the suspects. Cases involving juvenile piracy suspects should be handled under each state’s juvenile justice provisions, which may ensure that the juveniles’ rights are adequately protected, in accordance with international law described above.

‒

MEET THE AUTHOR

Milena Sterio is the Charles R. Emrick Jr.‒Calfee Halter & Griswold Professor of Law and Associate Dean at the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. Her research interests are in the field of international law, international criminal law, international human rights, law of the seas, and in particular maritime piracy, as well as private international law. She has participated in the meetings of the UN Contact Group on Piracy off the Coast of Somalia, and has been a member of the Piracy Expert Group, an academic think tank functioning within the auspices of the Public International Law and Policy Group. Professor Sterio is one of six permanent editors of the prestigious IntLawGrrls blog.