CAROLE CONCHA BELL

In our latest article in the series ‘Human Rights in the Age of COVID-19’, Carole Concha Bell of the Chile Solidarity Network brings our attention to the plight of political prisoners in Chile.

“From the solitude of this jail cell, with just a mattress and blanket but no sheets, I send a hug to my family and all those who have collaborated with my cause. I hope for the imminent release of everyone who has been jailed for participating in the October uprising.’”

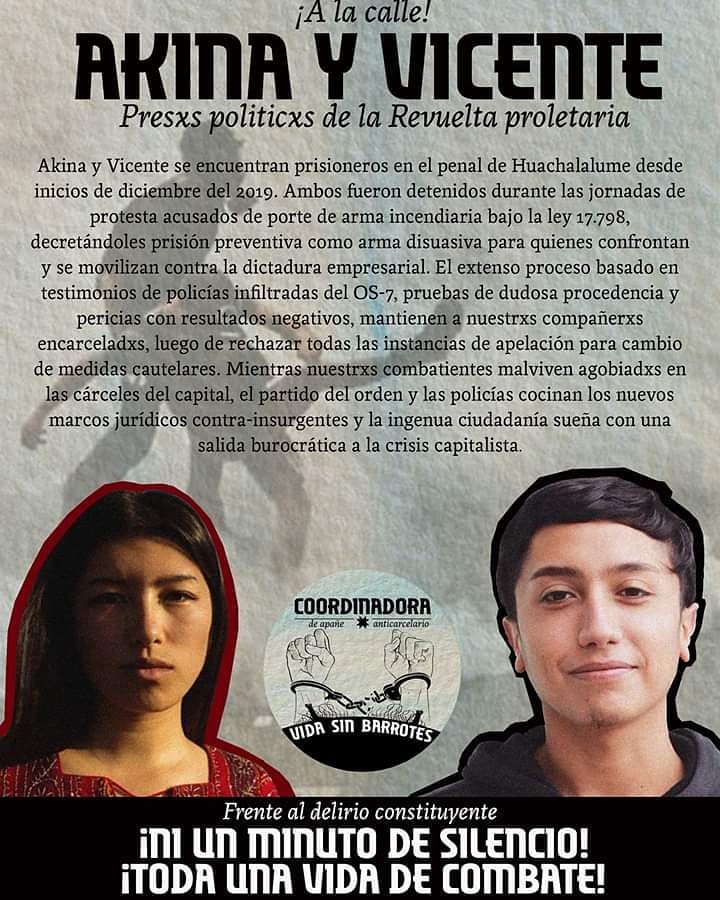

These are the words of Akina Nakamura, 25, a nursing student and yoga teacher currently incarcerated in Huachalalume penitentiary in Coquimbo, Chile. Akina joined a peaceful march in La Serena on December 4th 2019, when she was arrested and accused of carrying a Molotov. She has since been locked away in a Chilean Women’s prison accused of terrorism based on scant evidence and the testimony of an anonymous witness. But this is not an isolated case, at present there are approximately 2,500 people, many under the age of 21, being held in Chile’s prisons at extreme risk of contracting Coronavirus. With the death toll now hovering near the 7,500 figure and accusations of cover-ups around the true extent of virus spread, costing the health minister Jaime Manalich his job, the situation is spiraling out of control.

For decades the plush vineyards of Chile’s central region and clinical architecture of Santiago’s wealthy ‘Sanhatten’ district mask the reality of a nation in crisis: fifty percent of the economically active population earn less than 550 dollars per month, with the minimum monthly wage equivalent to 414 dollars. The pension system drawn up in 1982 has effectively left 80 per cent of Chilean pensioners living on around $400 per month. They are surviving on incomes under the minimum wage. The toll of living in a society defined by stark inequalities and unequal access to education and decent healthcare, have driven millions of Chileans to spill onto the streets to demand an end to social disparities, in what is one of Latin America’s richest countries. But protesters are now paying a heavy price for speaking out.

Chile’s authoritarian Government led by billionaire oligarch Sebastian Pinera, reacted to the social unrest and demands for a new constitution by declaring ‘We are at war’ and followed this by invoking Pinochet era laws to punish those voicing dissent. Between October and December of 2019 more than 20 people were killed at the hands of carabineros, thousands have been tortured, and hundreds more injured by projectiles fired directly at people’s heads, contravening international law. Five international bodies including the Institute of Human Rights Chile, Amnesty International, UN, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and HRW have filed reports citing the repression in Chile as the ‘worst since the military dictatorship’ and pressed for immediate reform of the police force. To date, none of their recommendations have been implemented. Instead Pinera has cited public order as an excuse to push though even more draconian law. On Thursday, November 7 2019, at the peak of the protests, President Piñera announced a new series of security measures meant to criminalise public protests. The laws include bans on barricades, blockades, looting, violence, and increased surveillance.

A key law at the centre of this wave of imprisonments for this new generation of the ‘enemy within’ is the Law for the Internal Security of the State (LES) implemented by the Pinochet regime in 1984. It penalises with prison those who “destroy or disable” means of transportation, alongside anyone who is seen to “incite or induce subversion of public order or revolt,” punishing those who “meet, arrange or facilitate meetings” that conspire against the stability of the government, and those who propagate “in word or in writing” doctrines that “tend to destroy or alter the social order through violence.”

The most draconian article within the LES penalises people who are deemed to “destroy, disable or prevent free access to bridges, streets, roads or other similar public use goods.” That law is being wholly applied to various forms of public incursion, from students who incite evasion of the subway fare to protesters who mobilise peacefully every day on the streets, blocking traffic. The Senate’s Public Security Commission has also approved a bill incorporating the crime of “public disorder” into the Criminal Code, imposing penalties of up to three years in prison for those who, “using a demonstration or public meeting,” paralyse or interrupt a public service of prime necessity, such as the subway, or throw stones, build barricades, or occupy private or public property.

Pinera’s government has been particularly harsh when dealing with student rebellion. In early 2019, the government increased police control to deal with student protests, which included identity checks on children from age 14. ‘Aula Segura’ or ‘Safe classrooms’ is a law that allows the expulsion of students or teachers that take part in demonstrations. It’s not uncommon for patrols of special forces to storm the grounds of schools and universities, harassing students and teachers and rifle through backpacks for evidence of political activity.

Furthermore, the anti-hood (capucha) law seeks to penalise anyone who “intentionally covers their face in order to hide their identity, using hoods, scarves or other similar elements” while participating in actions that “seriously disturb public tranquillity.” Since the use of masks to avoid breathing toxic tear gas is necessary for anyone venturing near downtown Santiago, anti-hood law legalises the arrest of peaceful protesters, guaranteeing their conviction.

By drawing on these draconian measures Pinera’s government prefers to ignore the root causes of the social unrest and instead outlaw protest, and strip citizens of their right to freedom of expression. The LES, anti capucha law and Aula Segura are the perfect tools with which to repress dissenters, using state terror as a deterrent.

At a time when public opinion has swung against police brutality and crowd control arms after mass protests in the United States over the killing of George Floyd, Chile is finding itself increasingly isolated, yet since the Coronavirus took hold in Chile, the state has responded with further repressive laws. Those breaking lockdown rules can face up to 3 years in prison, press and artistic freedoms have been violated making it ever more difficult to report on human rights abuses.

Prisoners like Akina are running out of time. Coronavirus is tearing through Chile, currently among the Latin American countries with the highest number of infections. But as hungry Chileans unable to work and feed themselves during the pandemic lift barricades and clashes continue in poor suburbs, the October uprising prisoners risk being forgotten and worst of all, succumbing to the virus.

Carole Concha Bell is a Cambridge-based writer, founding member of the Chile Solidarity Network and press officer for Mapuche International Link. For more information on this story, the campaign and how to help, please visit here. Follow Carole’s work @chiledissident