PASCALE PÉAN

Introduction

On 23 October 2018, the United Nations Human Rights Committeefound that banning the niqab, a veil worn by some Muslim women that covers part of the face, violated two Muslim women’s freedom of religion in France. This ban is one of many in France, such as the “burkini” ban and the ban on full-face veils, that have overwhelmingly affected Muslim women. Through the implementation and enforcement of these bans, the French state has seemingly limited not only the freedom of religion but also the freedom of movement of visibly Muslim women. Although the bans allegedly strive to promote women’s rights, France has drastically reduced the freedom of movement of many women by restricting them to private spaces. As most human rights can only be fulfilled with access to public space, freedom of movement and the ability to access public space is an essential right.

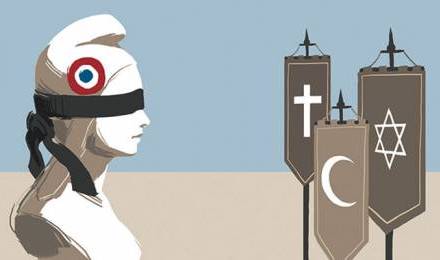

As an assertively secular state, France seeks to manage its religious population by limiting their visibility in public space. Upholding the values of laïcité, the French interpretation of secularism that encourages the complete separation of religion from the public sphere is often cited as a rationale for banning certain religious dress from public areas (Jung, 2016; European Court of Human Rights, S.A.S. v. France,2014). If laïcité is seen to be a vital aspect of French society, then the French government must discipline those who fail to meet these standards. Whether this discipline is done through public dialogue berating outwardly religious individuals or threatening to limit one’s freedom of movement, the inevitable degradation of the human rights of French Muslim women occurs (Foucault, 1994). The existence of these bans and the French public’s ability to vilify headscarves and full-face veils “as instruments of female oppression speaks to the place of Muslims in French society” (Jung, 2016: 6).

Discipline of visibly Muslim women

The French state disciplines religious-presenting women through targeted legislation for failure to comply with the secular guidelines of laïcité. Michel Foucault states that governmentality works through state practices of disciplining large populations. This disciplining occurs through the close management and regulation of populations as well as through disciplinary measures undertaken when the population fails to abide by the regulations (1994: 243). Since France is an assertively secular state, governmentality in France works to maintain a secular population. Religious groups in France are seen as having undesirable beliefs and practices, which are defined outside the borders of the dominant group. The state then uses this undesirability as a justification for exclusion and targeted legislation of religious groups (Fredette, 2014: 27). Those who the state defines as religiously undesirable are also seen as deviating from the state’s standard of secularism, thereby creating the need for targeted legislation (Selby, 2014: 452). This targeted legislation is apparent in the various religious dress bans and clothing laws that target Muslim women.

The targeted legislation of visibly Muslim women works as a mechanism to discourage the appearance of religiosity in France. However, the effects of this legislation are far too severe to be considered an appropriate or proportionate punishment for simply failing to be secular. Through using public space as a privilege granted to visibly secular individuals, these religious dress laws immobilize and reduce the sightings of veiled women. This also works as an effective silencing of women, particularly those with opposing views (El-Tayeb, 2011: 83). These religious dress laws work as a disciplining of both the bodies and minds of religious and non-religious women (Mondon, 2015: 408). Religious women are faced with the challenge of either abandoning their values in order to appear non-religious or standing by their religious convictions and being banned from public space. Meanwhile, women who appear non-religious witness the expulsion of religious women from public space as a cautionary tale of what happens when one dares to live differently.

This legislation of religious dress in France (particularly focused on full-face veils) is not proportionate, considering the small number of women who wear full-face veils. In 2010, the French Minister of the Interior estimated that only 1,900 women wore full-face veils at all (Selby, 2014: 454). For a national population of 65 million people that year, the clothing choices of such a small group should have never taken center stage (World Bank, 2017). Even if a larger percentage of French women wore full-face veils or other religious forms of dress, banning a group that already suffers from Islamophobia, sexism, and socio-economic issues from public space seems unnecessarily harsh (Teeple Hopkins, 2015: 161). In order to comply with international human rights standards that guarantee freedom of movement and promote equality, France must respect those who wish to be both publicly and privately religious.

Saving women through male dominance

Many French laws concerning full-face veils focus on the liberal feminist project of freeing Muslim women from both veils and the assumed Muslim men that force these veils upon women. However, this intense concern for Muslim women is not found when addressing women of Jewish, Buddhist, or Sikh backgrounds (Abu-Lughod, 2013). Why is the concern about women’s rights limited to women in Islam while other religions can be interpreted to contain misogynist aspects as well? Furthermore, portraying Muslim women as if they need to be freed or saved implies that they are being saved from something and delivered to something better: “Projects of saving other women depend on and reinforce a sense of superiority, and are a form of arrogance that deserves to be challenged” (Ibid: 47). Like the French laws, projects of ‘saving’ Muslim women typically happen through regulation and training. This gives way to a paradox in which women must be instructed in order to be saved and trained how to be free (Valdez, 2016: 19). These projects not only perpetuate stereotypes of Muslim women, but also echo colonial feminism, in which native women were coerced to leave behind their cultural traditions with the promise of becoming better, more advanced, and more liberated (Abu-Lughod, 2013: 49).

Supporters of the French veiling bans repeatedly referred to women’s rights and gender equality as a justification of the removal of full-face veils. Full-face veils are seen as a barrier impairing gender equality, which is itself seen as a constitutive aspect of both French values and public order (Valdez, 2016: 19). If full-face veils exist in a static space, where they can only be considered an impairment of gender equality, it is difficult to defend women’s freedom to wear them. In this mindset, religious accommodation is viewed as making room for the erosion of women’s rights (Selby, 2014: 445). Both the veils and the women wearing them exist in a state of static stereotypes, where gender inequality is a uniquely Muslim issue and domineering men force submissive women behind veils. French law assumes this, by placing penalties on wearers of full-face veils and even higher penalties on men convicted of forcing women to wear veils (Selby, 2014: 442).

By treating the wearing of veils as a crime with a perpetrator and a victim, women are never seen as truly autonomous: “the freedom of Muslim women and their capacity to reason are put into question because of their adoption of a particular religious ritual” (Valdez, 2016: 19). Because of some Muslim women’s choice to adopt a religious ritual, they are seen as submissive and unable to think on their own. How is it, then, that statements claiming to be feminist dare to put women in the same categories so often assigned by misogynist powers? In trying to liberate women, men and women are misunderstanding, essentializing, and restricting women. Liberal feminists that are seemingly burdened with their passion to liberate veiled women (by merely removing their veils) have yet to realize that fighting for women’s rights is not centered around women who look and think like them. Fighting for women’s rights also means fighting for a woman’s right to be different and uphold a different identity.

Standing up for women’s rights inevitably includes standing up for women who are marginalized. This does not mean forcing one’s way of life on another, but standing up for their autonomy and their right to live a life they consider to be worthwhile. This type of feminism recognizes and celebrates differences and intersections of identities, rather than trying to erase differences. Feminism is not a Western thought, born and confined to the West and Western religions (Abu-Lughod, 2013). Women wearing full-face veils can be just as free, or even more free, than women without full-face veils. Freedom is not dependent on clothing. The freedom from being forced to wear a full-face veil should not impair the freedom to wear a full-face veil, especially in the name of women’s liberation. If women are not given this freedom to wear what they wish, they go from the supposed dominance of one male to the actual dominance of another in the form of the male-dominated state that upholds patriarchal values by dictating what they should or should not wear.

The secular female body

The accessibility and visibility of a woman’s face and body is clearly important in French society. The regulation of female forms and religious dress are a means of achieving the idealized secular female body, which is heteronormatively produced for male consumption. Foucault argues that governmentality includes the “surveillance and control as attentive as that of the head of a family over his household and his goods,” but on a larger scale (1994: 234). This desire for intense surveillance and control of populations within a state explains why the French state has taken such a heightened interest in the dress of individuals. Specifically, when these individuals are outwardly religious in a secular state, the state takes interest in managing and minimizing the appearance of religiosity. “The state has a clear interest in shaping ‘acceptable’ sexuality across public and private spheres as a central component in the production of its citizens” (Selby, 2014: 452).

© Arnaud Tracol

An aspect of state management of acceptable sexuality focuses on the concept of beauty. The state forms and guides subjects’ beauty and personhood as a precursor to providing rights (Nguyen, 2011: 369). The beauty shaped by the state creates a standard of what it means to belong to the state and have one’s rights protected by the state. The French bans of full-face veils and other religious symbols construct women’s beauty in ways that are “observant of secular femininity, rather than visibly religious” (Valdez, 2016: 20). This ideal form of a secular French female body is a body that is easily visible without being veiled or modestly covered. This idealized secular female body perpetuates heteronormative, male-centered ideas of femininity. These notions of femininity, particularly in the French setting, include not remaining a virgin into adulthood or until marriage and the ability to publicly seduce (Selby, 2014). The importance of French femininity is noticeable on a state-level with focused legislation on women who are not seen as attempting to accomplish the idealized secular female body. But if two factors of this French secular female body include the ability to seduce or be a non-virgin, how will religious dress bans effectively accomplish this? A woman does not suddenly become a seductive non-virgin the moment she is unveiled, just as a seductive non-virgin can be a veiled woman.

Notions of dignity and rights are also intertwined with the way a woman chooses to present herself. “Objections to the burqa [a loose garment worn by certain Muslim women in some Islamic traditions that covers the entire body and head] include that it hobbles the feminine body, curtails freedom of movement, and inhibits both range of motion and access to public space” (Nguyen, 2011: 368). Following this logic, it is then counterintuitive to punish a woman for wearing a burqa or niqab by curtailing her freedom of movement and banning her from public space. Furthermore, the visibility of one’s body does not indicate ones access to human rights. And even the promoted idea of nakedness that is focused on seduction and the lack of veils does not promote true nudity. Even a secular female face is typically encouraged to be veiled by some form of makeup (Selby, 2014: 448). Rather than anti-veiling laws focusing simply on cloth veils, the laws also focus on a societal standard of what it means to be a body worthy of existing in public space in France.

Impaired civic membership

French veil bans impair civic membership of Muslim women and violate their human rights (for a different conclusion, see the S.A.S. v. France case of the European Court of Human Rights, which upheld France’s ban on full-face coverings). Through targeting visibly religious individuals, French veil bans violate Articles from at least three international human rights documents. Article 1(1) of the UN Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief and Article 2(1) of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious, and Linguistic Minorities state that individuals should have the right to manifest their religion in both private or public, without fear of discrimination. Although these human rights documents are not binding, they work as a guideline of standards states should hold. Moreover, the legally binding International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, ratified by France in 1980, states that all peoples have a right to cultural development as a practice of their self-determination. Religious practices and dress could easily be included in this article, as religious and cultural practices are often overlapping. Religion is also an important part of what some consider to be essential in their vision of living a good life, which also contributes to their self-determination.

In addition to the human rights documents that go against French veil bans, the lack of access to public space for full-face veiled women can also be interpreted as a human rights violation. Public space should be places where community members of diverse backgrounds can act out their freedoms and enjoy their community. “Liberty, equality, tolerance, and democracy crucially depend on the availability of space that is accessible to everyone. Free and equal access to public space is a foundational element of any liberal democracy” (Moeckli, 2016: 413). If veiled women only have freedom in private spaces, they are not truly free. Article 15(4) of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, Article 13(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 12(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights guarantee freedom of movement as a human right. Without access to public space, this right cannot be fulfilled.

Conclusion

Even if the discrimination faced by Muslim women in France due to these bans was unintentional, indirect discrimination is still discrimination. Article 3 of the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief states that “discrimination […] on the grounds of religion or belief constitutes an affront to human dignity […] and shall be condemned as a violation of the human rights and fundamental freedoms proclaimed in the [Universal Declaration of Human Rights] […]”.

Discrimination also impairs civic membership by encouraging conditional citizenship. Legal citizens who wish to be religious suffer from lessened rights, social inequality, and physical exclusion (Fredette, 2014: 27). Without full civic membership, French Muslim women (particularly those who wear veils) do not have a true claim on their human rights. France must protect its religious minorities, not ignore them or confine them to private space. Without the state’s protection, the human rights of Muslim women in France are meaningless.

—

Meet the author

Pascale Péan is a researcher on human rights issues related to Israel-Palestine and runs a social enterprise called The Decolonize Project. She has a BA in Intercultural Communication from Pacific Union College and was awarded a merit from the LSE for her Human Rights MSc. Find her social-enterprise at thedecolonizeproject.com or on Instagram @thedecolonizeproject.